Imported printed and painted Indian chintzes directly influenced Western quilts’ materials and design. When Europeans first encountered printed cottons from India during the early 1600s, they marveled at the bright, colorfast, washable fabrics. By 1800 cotton prints soon replaced silk and wool as the preferred material for decorative bed-coverings. Today, cotton is still the dominant fabric in quilts.

Imported printed and painted Indian chintzes directly influenced Western quilts’ materials and design. When Europeans first encountered printed cottons from India during the early 1600s, they marveled at the bright, colorfast, washable fabrics. By 1800 cotton prints soon replaced silk and wool as the preferred material for decorative bed-coverings. Today, cotton is still the dominant fabric in quilts.

Indian textiles influenced quilt design also. Palampores—printed cotton bedspreads with a large central design surrounded by a border print—are reflected in the Medallion format of many quilts made between 1800 and 1850, in both chintz appliqué and pieced quilts.

India's woven Kashmir shawls also proved influential. The pine-cone motif, now known as the paisley, made up the primary design element of the shawl. Produced by highly skilled weavers of the Kashmir region of northern India, these shawls became the height of fashion for early 1800s European women. The French Empress, Josephine, was said to have owned 400 of them!

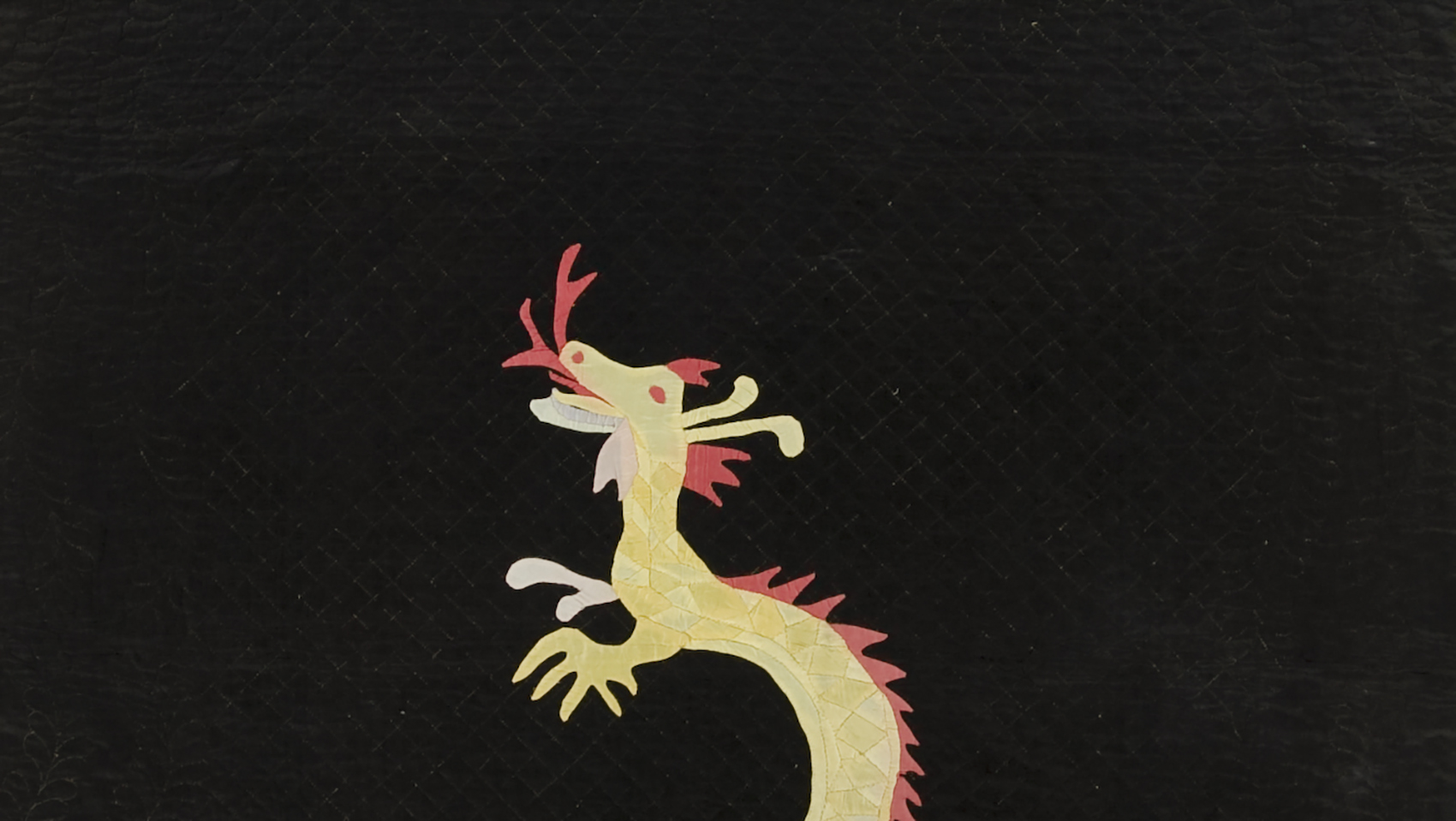

Printed and painted palampore, probably made in India, c. 1750-1770, IQM 2008.040.0219, acquisition made possible by Robert & Ardis James Fund at the University of Nebraska Foundation, partial gift of Sara Rhodes Dillow